In the October issue, I discussed pricing strategies and provided recommendations on how to price a product and why it's so important. The formula is quite simple: price products competitively, maybe a little lower if possible and definitely a little higher if the product is proprietary. Selling a product at a higher price than your competitor is known as "prestige pricing." This can only be done, however, if the customer buys an acceptable quantity at the higher price. This would mean that a prestige priced item is popular with the customer, resulting in a top-seller within its category.

There are two key criteria for pricing any product; (1) set the price so that you are getting the maximum contribution margin and (2) make sure the product quantity sold is at the top of the product category. A product must be able to deliver both of these to be considered a winner. Not all products sold are going to meet these criteria, but consumer preferences change as do the product costs, so a periodic performance review by category is beneficial.

Sounds easy, but the reality is the customer must perceive the pricing to be fair relative to what they think the price should be for any product. This perception can be based on a variety of factors. They include brand recognition (signifying quality), size and quantity, and knowledge of what the same product sells for at other locations. Today's consumers are very savvy about products being sold, and generally scrutinize ingredients, nutrition, sizes and prices.

Additionally, do not dismiss the value of convenience that you provide, particularly in the vending, micromarket, onsite foodservice and office refreshment segments. If a customer does not have to leave the building and can purchase what they want from you, then it has value and allows you to "gently" elevate prices over the competition.

Price elasticity must also be considered when deciding on a product's price. When the price goes up on a product and the quantity sold is less, then the product is elastic. When the price goes up on a product and the quantity sold remains the same (or increases) then the product is inelastic. This is the balance for which you should strive when pricing a product.

Unfortunately, operators of vending, OCS, foodservice and micromarkets exist in an elastic pricing world, and this where the "psychology of pricing" comes into play. The starting point for pricing a product should include some knowledge of what the customer wants (not what you like) and is willing to pay for it (customer perception). You do not want to sell a slow-moving product or one that has a low contribution margin.

As mentioned earlier, selling proprietary products, items that no one else has or your own spin on a product, could give you a big pricing advantage. However, the consumer also wants brand-name products, which is the real pricing challenge because the competition sells them, too.

Incremental Pricing

There are incremental pricing targets used by retailers that are relatively universal. These increments are directed toward the last two numbers of a price -- .49, .69 and .99, for example.

It seems that the price value of a product for a consumer is cheaper if it is under 50¢, 75¢ or the next dollar. For instance, a candy bar priced at $1.49 is perceived to be cheaper than one at $1.50, and the same is true with $1.69 vs. $1.75 and $1.99 vs. $2.00, even though the price differences are only pennies.

When pricing a product at $2.95 rather than $2.99, you must consider, 4¢ per transaction is lost. It amazes me that operators like the ending number of 5 more than 9, but customers do not perceive the 4¢ difference as a deal breaker.

Take a look at the two potato chip examples here.

src

src

Based on the first example, you can gain 7¢ for each transaction of the larger size bag of chips.

In addition, if you increase the selling price of the larger bag by 9¢, you actually gain 16¢ per bag of contribution margin and still stay under the $1.00 threshold.

Calculation: Sell for 99¢ rather than 90¢ and you gain 9¢ per transaction times how many transactions per year = ? $'s

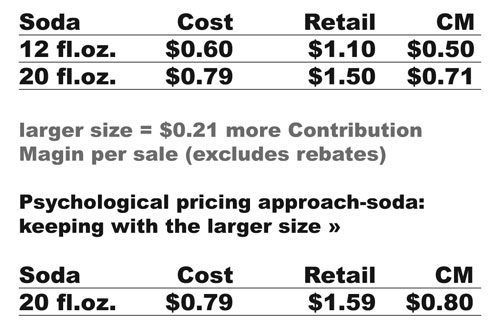

In another example, let's look at soda, starting with two sizes.

src

src

Calculation: If you sell for $1.59 rather than $1.50, you gain 9¢ for every transaction times how any transactions per year = ? $'s.

Oh, I can hear it now from some vending operators: "We don't deal in pennies!" Wider use of cashless payments technology makes this pricing model possible. As for micromarkets and onsite foodservice installations -- no problem!

In both examples, I have applied the psychology of pricing to increase the sales dollars and contribution margin, and I assure you that there would be no loss of quantities sold. These increases are referred to as gentle price increases.

In summary, gentle price increases in pennies will yield additional dollar profits over time and selling larger size products provides pricing advantages. Those are the two takeaways this month. In my next article, I will talk more about the psychology of pricing by focusing on the mechanics of when, why and how to make product price adjustments.

Editor's Note: This is the second article in a three-part series about product pricing. Jerry McVety's first article --"What is Your Pricing Strategy? Establish A Product's Cost, Then Apply Fundamental Valuing Methods" -- is now available online.

JERRY McVETY is founder of McVety Associates, an international foodservice and hospitality consulting firm. He has held a variety of executive positions in the foodservice industry. McVety, a Knowledge Source Partner in the National Automatic Merchandising Association, is also an active speaker on the industry lecture circuit. He can be contacted at jmcvety@mcvetyassociates.com.