In the winter of 2009, six weeks after she was the victim of a home invasion, Stephanie Reeves was in a London, Ont., convenience store when Kaylei Marie MacDonald walked in and instantly became a cautionary tale in forensic eyewitness psychology.

Security footage shows the two women in a strange standoff for a few seconds, before Ms. MacDonald turned around and walked out.

“I know her. Those eyes,” Ms. Reeves told the store clerk. “I’ll never forget those eyes.”

The clerk took Ms. MacDonald’s licence plate, and Ms. Reeves told police this was the woman who ransacked her home while a masked man, as yet unidentified, held her at knifepoint.

“I think we both realized we were looking at each other in the face,” Ms. Reeves, now 34, told police a few days later, when she picked Ms. MacDonald’s face out of a lineup. “I guess her reaction was to leave the store.”

This chance meeting seemed to have cracked the case, but Ms. MacDonald, then aged 20, denied any knowledge of the crime. She told police she left the store without buying anything because she recognized the clerk as someone who would not sell her cigarettes without the ID she did not have. A jury, however, found her guilty as charged.

Now, in a judicial ruling that illustrates how vexing the supposedly simple task of facial recognition can be when someone’s freedom is on the line, the Ontario Court of Appeal has overturned Ms. MacDonald’s convictions for armed robbery and break and enter, and ordered a new trial.

The ruling, which criticizes the trial judge for his simplistic guidance that jurors use “common sense,” also highlights a troubling legal trend. Leading forensic psychologists say the same judges who will happily let experts explain blood spatter or DNA or psychosis are reluctant to the point of stubbornness to allow expert testimony on eyewitness frailty.

“They’re more than reluctant. It’s closer to a policy,” said Roderick Lindsay, co-editor of The Handbook of Eyewitness Psychology and a professor at Queen’s University.

“Almost never,” said Don Read, a professor of psychology at Simon Fraser University and an expert in the forensic science of memory. “They believe that it’s common sense.”

In the U.S., expert testimony is routine, Prof. Lindsay said, and in California almost obligatory. In Canada, there are guidelines and precedents for how a judge should caution a jury, but in this case they were not followed.

Eyewitness identification “is so risky to be the sole basis of a conviction,” Prof. Read said. “I’m just kind of shocked actually that there would be a conviction based upon an eyewitness identification only. It’s very unusual in this day and age.”

The judge, who died after the verdict but before sentencing (Ms. MacDonald got two years, much of which she has already served), made several errors in his jury instructions, according to the Ontario Court of Appeal. All involved the testimony of the key witness, the victim, Ms. Reeves.

Confidence is no guide to accuracy, and the identity eyewitness who is 100% confident poses the gravest of problems

For example, Ms. Reeves made an in dock identification, that dramatic moment when a witness points at the accused from the witness box. The law regards these moments as “deceptively credible,” and they ought to trigger a special caution, which the judge never gave.

The judge also failed to warn that the lineup could have been contaminated by the convenience store encounter.

Prof. Read said judges often fail to understand that eyewitness memory is an “inferential process.” It is like solving a problem, drawing a conclusion, discovering something. It can be wrong even when it feels right.

“When we make a judgment of familiarity, we then make an attribution about why that person is familiar to me,” Prof. Read said. “And then you sort of search through your mind and try to find where that person is from.”

Confidence is no guide to accuracy, and for the courts, the identity eyewitness who is 100% confident poses the gravest of problems, because they are so convincing to jurors. This is where common sense can most easily lead to error.

“If that person who is now in the photo spread becomes her memory for who she saw in her house, that’s true contamination, because now we’re working backwards, and whatever she does remember about the house person is completely taken over and subsumed by this very recent current experience that she’s had with this other face. And so that’s the person she’s going to recall,” Prof. Read said.

The judge failed to warn the jury of this, and he undermined the warning he did give by urging jurors to use their “common sense” when weighing the “considerable differences” between Ms. Reeve’s initial description of the female robber and Ms. MacDonald’s actual appearance.

Ms. Reeves said the robber was 18 to 24 years old, thin, 5-foot-9, with light brown hair, dark brown eyes and a good complexion. Ms. MacDonald is about the right age, but 6-foot tall with blue eyes.

As the appeal court put it, “While juries are generally encouraged to use their common sense, the very reason for this special caution with respect to identification evidence is that such evidence poses problems that fall outside the common experience and knowledge of jurors.”

The robbery occurred around 9 p.m. a week before Christmas 2009, when Ms. Reeves was invited by a neighbour to go for a cigarette outside her London, Ont., townhouse. Her eight-year-old son was upstairs. A man with a nylon stocking over his head appeared at the door, forcing them back inside at knifepoint, demanding money and pills. The neighbour told police she lay face down through the entire 10-minute ordeal, and did not see the woman who came in next, and went rummaging in the basement. The robbers left with a video game system, two cellphones and a safe box with $500 in coins.

Ms. Reeves saw the woman clearly, and said she was struck by her big dark brown eyes and her cocky demeanour. It was the same demeanour she saw in Ms. MacDonald at the 7/11.

Stress can heighten focus, but it can also send it in unusual directions.

Prof. Read said a person’s accurate recognition of a face depends on how much “processing” they were able to do when when they first saw it, how much sensory input they had to “encode” the memory. “Weapon focus” is a typical problem, as is the fleeting nature of some crime.

‘I’m just kind of shocked actually that there would be a conviction based upon an eyewitness identification only. It’s very unusual in this day and age’

Prof. Lindsay, who has run training sessions in eyewitness frailty for most Canadian judges, said they are most keen to learn how to tell if a witness is right or wrong.

“And the answer to that is you don’t. There is no infallible method,” he said. Circumstantial factors, like lighting or duration, are relevant, but Prof. Lindsay said his main message is that eyewitness identification should be treated as an issue of due process.

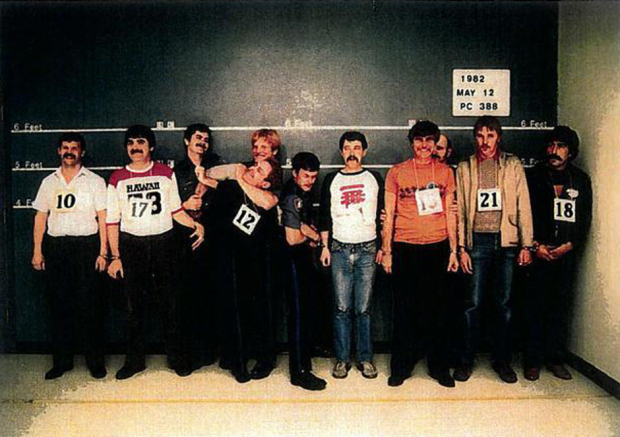

Failed lineups, for example, should be disclosed. They should definitely be “double blind,” in which the conducting officer does not know the “right” answer. The witness should be told the guilty person might not be here, but not how many options there will be. Their answers should be yes or no, not maybe, and they should be quizzed immediately about their confidence in a match. Lineups should be prepared based on the witness’s initial verbal description, not whatever mugshots are available.

Another major factor is whether a lineup is done one picture at a time, or with all of them spread out before the witness.

Simultaneous lineups are discouraged, because people tend to look for the person who most resembles their memory. These have shown a slightly higher match rate in experiments, but Prof. Lindsay and others argue this is due to guessing, which will sometimes be right. In sequential lineups, witnesses do not guess. They only recognize or fail to, and so the number of false identifications is greatly reduced, which is why this is regarded as the fairest and safest method.

“You don’t need a simultaneous lineup unless you don’t really know what the person looks like,” Prof. Lindsay said.

Ms. MacDonald’s lineup was properly sequential, but woefully misleading, as the ruling shows. It is not clear if the Crown will proceed with a retrial, but for the court, the lesson is learned.

As Prof. Lindsay describes it, “simple assumptions are almost always wrong in the eyewitness area.”

National Post

• Email: jbrean@nationalpost.com | Twitter: JosephBrean