By SARAH NASSAUER

Did you really eat that many cookies?

Packaged-food makers might know the answer, even if you don't. Aware that people snack a lot throughout the day, they continue to introduce new packaging that encourages consumers to eat their food anytime they have an urge to nibble, what some executives have dubbed "hand-to-mouth" eating.

Why is it so hard to tell how much you're eating when you snack? Sarah Nassauer and INSEAD professor of marketing Pierre Chandon join Lunch Break with a look at why it's hard to eat just one of anything.

The psychology behind how this affects eating behavior is complicated. Sometimes small amounts of food could drive you to eat more. There are cues savvy snackers can detect.

Hershey Co.

learned that individual wrappers on bite-size candy were getting in the way of people eating candy in certain settings, like in the car. The company responded with Reese's Minis, a small, unwrapped version of its classic Reese's Peanut Butter Cup, in a resealable bag. It facilitates "I-can-pop-one-in-my-mouth, on-the-go type of behavior," says Michele Buck, senior vice president and chief growth officer for Hershey.

As part of what the company calls its "hand-to-mouth platform," it recently introduced Rolo Minis, Twizzlers Bites and Jolly Rancher Bites—all small versions of the candies in resealable bags. Sales of unwrapped miniature chocolate rose about 14% in 2012 compared with the previous year, far faster than the 4% growth of miniature, wrapped chocolates, according to Nielsen data compiled for Hershey. Kit Kat Minis are coming in May.

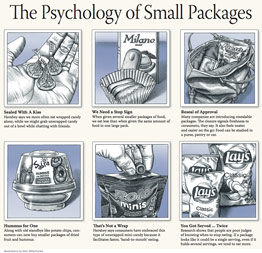

The Psychology of Small Packages

View Graphics

Packaging is so influential that even a subtle hint seems to nudge people to stop eating. Researchers fed college students watching television Lay's Stax with a red chip placed at various intervals throughout the canister in a 2012 study. Some students got regular canisters without any red chips. Students given canisters with red chips ate less than half the amount than those without red chips. When questioned later they also more accurately described how much they ate. An "artificial barrier" helps eaters decide when to stop, says Andrew Geier, lead author of the study published in Health Psychology.

The urge to eat to the bottom of a bag appears to wane when a package is so large it is clearly not a single serving size, Dr. Geier says.

For years people have been shifting their eating habits to include more snacks on the go. Their options have expanded exponentially since the introduction of small bags of potato chips or pretzels for lunchboxes years ago. Target Corp.

is putting foods like freeze-dried fruit and granola bars into single-serving multi-packs. Smaller packs appear to be boosting consumption of hummus, "not a staple of the American diet," says Ken Kunze, chief marketing officer for Sabra Dipping Co., a joint venture between Strauss Group and PepsiCo Inc.

The company offers its hummus and salsa in "Grab and Go" portions, small cups paired with pretzels or chips. More recently it introduced two-ounce hummus cups.

![[image]](http://psycholo.gy/wp-content/images/cache/0/25/532/e39e3_PJ-BN713_BITESI_D_20130415164314.jpg) Robyn Wishna

Robyn Wishna

Researchers found that college students ate less and could better guess how much they ate when canisters of potato chips were spaced out with special red chips.

Brian Wansink, director of Cornell University's Food and Brand Lab, studies how size and packaging affect consumption. In one experiment of his, moviegoers given two-week old popcorn ate 34% more from large buckets than out of medium-size buckets while describing it as "stale" and "terrible." The study showed that those served fresh popcorn ate even more out of the larger buckets.

People are woefully inept at knowing when to hit the brakes with food. They eat to the bottom of the bowl or bag if that seems like a logical meal or portion size, a behavior dubbed "unit bias" by academics. New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently cited similar behavioral tendencies as a reason for his attempt to restrict the size of large, sugary soft drinks.

Certain types of eaters—people who are concerned about how they look or who aren't naturally good at controlling their eating—see bite-size pieces of food as "zero calories." In doing so, they tend to eat more than a regular-sized version of the food, says Pierre Chandon, a marketing professor who studies eating behavior at Insead, an international business school based in France.

"Twenty-five calories is not a serving, so we nibble without thinking we are eating," he says.

Small packages of food can slow down impulsive eating. "You might think, 'Oh wait, I'm not supposed to eat two of them,'" because you have to open a new package or wrapper, Mr. Chandon says.

But Hershey executives say their "hand-to-mouth" products are boosting company sales because people eat their candy more often, not necessarily more each time. Consumers like that the products with resealable packages help them avoid tiny wrappers or spilled candy rolling around the floor of cars or in purses, a spokeswoman for the company says. When consumers see a resealable pack they often think the product will stay fresh longer.

Researchers say it is unclear how resealability affects eating behavior, but it could encourage eaters to slow down because they know they are supposed to save some for later. Walgreen Co.

says it will shift its Nice brand nuts from canisters to resealable bags this summer. Some consumers eat less because they "open it, dump it out and reseal it," says Jim Jensen, vice president of global partnerships at Walgreens. "Others would say that it was quite easy to open and say I'm just going to eat the whole thing."

Kristy Louridas is a high-school physical education teacher who reaches for Reese's Minis in resealable bags to satisfy her sweet tooth after hard workouts or dinner. "When I am ready to get that fix those wrappers are just an inconvenience," says the Wayne, N.J., resident, later adding, "I'm probably eating a lot more than I normally would."

The bag is already "open. It's just like potato chips. It's fair game. It's mindless," she says.

Write to Sarah Nassauer at sarah.nassauer@wsj.com

A version of this article appeared April 16, 2013, on page D1 in the U.S. edition of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: The Psychology of Small Packages.