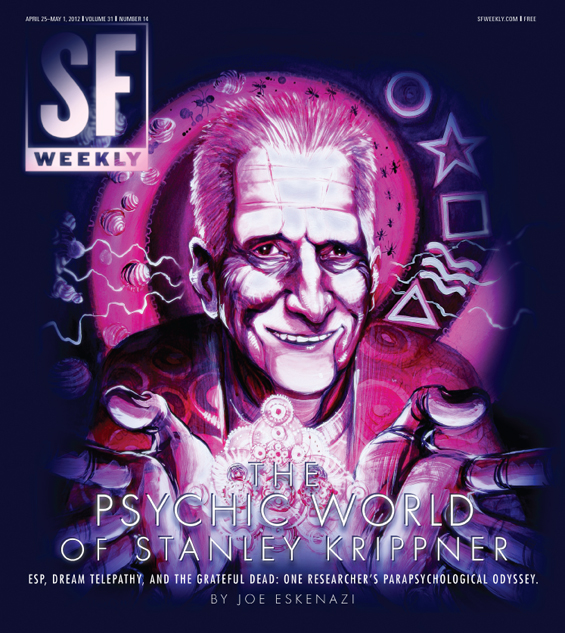

Illustration by MEAR ONE.

June, 1970: an interesting time. Behind the scenes at the Grateful Dead Festival Express tour: an interesting place. But if you want to see something really interesting, stroll past the roadies, the groupies, the freaks. Buttonhole the clean-cut, older guy in a suit. His name: Stanley Krippner.

Like this Story?

Sign up for the Weekly Newsletter: Our weekly feature stories, movie reviews, calendar picks and more - minus the newsprint and sent directly to your inbox.

You could see Krippner at scores of Dead shows. But at this one, you could see more. "Stan and I are backstage, and I look down at his sportcoat — he's wearing a really natty sportcoat — and there's a whole family of ants living in his breast pocket," recalls Bill Kreutzmann, one of the Dead's drummers. "So I say, 'Hey Stan, you've got a whole entourage of ants living in your pocket, you know that?' And he says, 'They come and they go. It's a whim thing. Some people see them and some people don't.'"

Kreutzmann chuckles, savoring the memory. "You could see anything around Stan. Anything was permitted."

Not quite two months later, the Dead debuted a song at the Fillmore in San Francisco called "Truckin'," which contains a line that's crossed the minds of so many people who, suddenly, find themselves in the present: "What a long, strange trip it's been." They weren't thinking of Krippner — unless, of course, it was a precognitive message somehow beamed to 1970 from the current day. Krippner would be the first to admit this is improbable — but perhaps not impossible. After all, around him, you can see anything.

For the better part of the past 40 years, Krippner, 79, has been a psychology professor at San Francisco's Saybrook University, a small graduate school near Jackson Square established in 1971 by the founders of psychology's humanistic movement. He has penned close to 1,000 papers on subjects as far-reaching as childhood creativity, combating soldiers' post-traumatic stress disorder, and worldwide shamanistic rituals. He has won more laurels from more organizations than he can keep track of, including several lifetime achievement awards from the American Psychological Association — the world's largest organization of psychologists and the definer of mainstream thought in the field.

And yet, among Krippner's cavalcade of papers are the following eye-openers: "LSD and Parapsychological Experiences," "The Paranormal Dream and Man's Pliable Future," and "An Experiment in Dream Telepathy with the Grateful Dead." (That last one, perhaps the only scientific study undertaken at the behest of Jerry Garcia, was published in the incomparably titled Journal of the American Society of Psychosomatic Dentistry and Medicine).

Krippner has traveled to every continent, save Antarctica, to participate in mind-altering tribal ceremonies or investigate "psychic claimants," and ventured behind the Iron Curtain to inspect "psychotronic generators" built to store and harness "psychic energy."

He has established a firm standing in the realm of parapsychology — the scientific study of psychic phenomena generally known as extrasensory perception — akin to the Dead's place in the pantheon of rock 'n' roll. Among both "advocates" and "counter-advocates" of ESP, his decade of meticulous experimentation with "dream telepathy" is viewed as some of the field's strongest and most methodologically sound work of the 20th century.

"Stan belongs on the Mount Rushmore of parapsychology," says fellow ESP researcher Charles Tart. James "The Amazing" Randi, perhaps the world's most prominent skeptic, also offers Krippner his benediction: "There are so few things in this field you can depend on, and there are so many people who are prejudiced and biased. But I can depend on Stan. And I don't think he's biased at all." In 1981 Randi bestowed on Tart a "Pigasus Award" for achievement in pseudoscience; they are not, to put it mildly, bosom buddies. But both consider Krippner a friend.

There are mystic healers perched on jungle mountaintops and tweed-suited aristocrats of academia perched within ivory towers. There are strident "believers" who equate a refusal to accept ESP as established truth with scientific bigotry and dubious scholars who insist the tenets of parapscyhology would undermine the laws of physics that gird our universe. And Krippner is the hub that connects them all. Like the shamans he studies, he moves effortlessly between any number of worlds. And what has his long, strange trip led him to believe? "To be very frank," he says in his unusually high-pitched, youthful voice, "I don't believe in much of anything."

When it comes to the study of the paranormal, Krippner — the field's elder statesman and author of some of its foundational studies — says "I am not a believer." He likes to "play" with ideas. "But just because I play with ideas does not mean I accept those ideas." Krippner has spent the better part of his career — and life — literally chasing a dream. But, after so many decades, the validity of his and others' ESP studies are like an ant creeping through his jacket backstage at that Dead show of so long ago: Some people see it and some people don't.

When Krippner discovered federal agents were monitoring him, he took to writing letters in triplicate to his Soviet parapsychologist colleague Vladimir Raikov. On the second copy he'd pen "For the CIA." On the third he inked "For the KGB." Raikov, of course, received just the one, unmarked letter. This remains a source of great mirth for both men.