The following blog post, unless otherwise noted, was written by a member of Gamasutra’s community.

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company.

Much to the annoyance of many gamers, whether video game violence causes real-world violence is a frequently studied topic in psychology. A definitive answer to this question, though, is still missing despite the fact that psychologists have been looking for one for decades.

Or rather, there's a lot of disagreement. Many politicians, researchers, and children advocacy groups point to lab studies, surveys, and meta analyses that show violent and aggressive behaviors follow exposure to violent games (e.g., Anderson et al., 2010) and that their case is incontrovertible. Other researchers say that they can ...controvert it. Is "controvert" a word? Let's say "controvert" is a word. They do this by pointing to other studies and meta analyses that fail to show a link, as well as flaws in the theory and experimental designs of the opposing camp (e.g., Ferguson Kilborn, 2010).

The details would have to be covered in a separate post, but the point is that the results of research on violence and aggression in games are mixed. There are several possible reasons why, but when I recently surveyed this literature it occurred to me that one reason may be that these studies have historically taken a very unsophisticated view of video games. Games differ widely in their design and so they surely differ widely in the ways that they interact with us and affect us psychologically. Some research, for example, shows that the context of the violence matters, and that shooting zombies while defending a teammate may affect our internal mental state differently than shooting the same zombies with the same weapons for no other reason than for sport (Gitter et al., 2013).

But it might be even more fundamental than that. A 2004 study by several of the biggest supporters of the "video game violence leads to real-world violence" camp found the results they were looking for when they had some subjects play a nonviolent game and others play a violent one. The researchers found that those who played the violent game had more aggressive thoughts and moods than those who played the nonviolent one. But let's take a closere look. In the nonviolent game, Glider Pro 4, players use just two keyboard keys to guide a paper airplane through a simple, two-dimensional environment. The violent game, Marathon 2, is a standard first-person shooter where players uses a mouse and 20 keys to navigate through a complex, three-dimensional environment.

There is a possible problem with this design. The researchers concluded that the violent nature of Marathon 2 was to blame for the increase in aggressive thoughts and mood, but it might have been that the complex nature of the controls were too much for new players to feel like they could do what they wanted in the game. This could then lead to frustration and a slightly hostile mood. In research parlance, this difference in the control complexity between the games is known as a "confound" because it offers an alternative explanation for the results.

This is exactly the thought that Andrew Przybylski (pronounced "Shuh-Bill-Skee") and his colleagues (pronounced "colleagues") had, and it lead them to an interesting study that was just published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. (Przybylski et al., 2014). In that study, they wondered how much frustration over one's inability to master game controls contributed to aggression, as opposed to the violent content of a game.

Przybylski and his fellow researchers used self-determination theory as a guiding framework for their research. In short, this theory posits that people are motivated to play video games to the extent that they scratch three psychological itches: the need to feel competent at what you're doing, the need to feel like you have meaningful choices when deciding how to do it, and the need to feel connected and related to others in the process. The researchers posited that when controls are difficult to master, it thwarts the need for competence. This leads to frustration. Frustration leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate eventually leads to blowing up Alderaan just to show some uppity princess who's boss.

To test this idea, Przybylski and his colleagues conducted a series of seven experiments, including a recreation of the Glider Pro 4 vs. Marathon 2 study described above. They also modified Half-Life 2 Deathmatch to create a nonviolent version where opponents were painlessly tagged and teleported to a penalty box instead of being blown to bloody bits. My favorites, though, were Studies 3 and 6, where they had subjects play the most nonviolent game imaginable, Tetris, but then screwed with them.

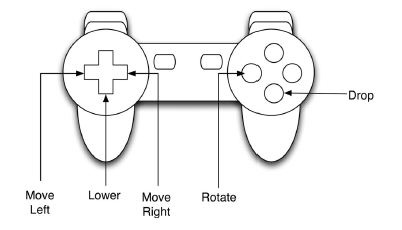

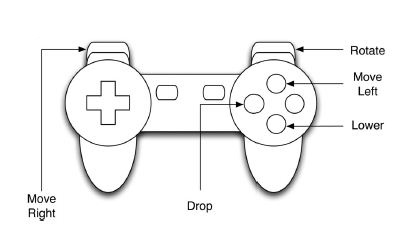

In Study 3, half the subjects played Tetris with normal, intuitive controls (see Figure 1 above) while half of them played with controls that were deliberately made to be counter intuitive and difficult to master right off the bat (see Figure 2 below). Just imagine trying to remember that the triangle button was for moving left, but that the left trigger was for moving right and the square button was for instantly dropping a block to the bottom of the screen --all under constant time pressure.

In study 6, the researchers moved beyond thwarting competence just by making the controls tricky; they actually increased the difficulty of the game. Subjects once again played Tetris, but for some of them the researchers thwarted their sense of competence by modifying the game so as to analyze the situation at the bottom of the board then give them the absolute worst possible block. Need a long, skinny block to slide into a 1x4 gap and complete four rows at once? Screw you. Here's a 2x2 block. Feeling aggressive now?

All throughout the seven experiments, the researchers included measures of both control mastery, competence in general, and aggressive thoughts, emotions, and mental states. The short version of the results is that video games could make people feel aggressive and think violent thoughts simply by thwarting their sense of competence, either through difficult to master controls or general difficulty. This was true even in the absence of violent imagery.

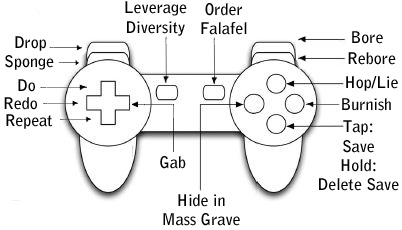

This makes a lot of sense to me. Many of us have been in multiplayer matches where your team just plain sucks, and no matter what you do you can't keep the opposition off the capture points or away from your flag. That undermining of your competence is frustrating and leads to rage quitting. So can difficult to use controls in any game. Just recently I was playing through the new Thief game and got frustrated with it when I couldn't line Garrett up to jump up and grab a dangling rope so I could get him away from a patrolling guard. I actually pounded my desk in frustration after the third attempt because I felt that this should be SO SIMPLE yet I couldn't do it. I felt like I was playing with this kind of control setup:

It's worth noting that Przybylski et al.'s 2014 paper doesn't address the question of whether or not violent games can make one violent, either in the short or long term. For example, it didn't look at whether violent and nonviolent games with equal difficulty and frustration potential could affect children the same or differently. But that wasn't necessarily the intent, Przybylski told me in an e-mail. The point was to show that games are complex, as are our interactions with them, and there are many theories about what makes for fun, frustrating, or enjoyable game beyond just how much red is on the screen. Alternative explanations for the effects of video game violence abound, and psychologists studying video games needs to better understand their nature and systems before designing research on them. This is why some of the best research on video games and psychology is starting to come out of people who grew up with the hobby and now getting established at universities and labs.

The violence in video games scene needs to move beyond simply "do they or don't they" and look more carefully into what qualities of the game might or might not be more important for a variety of outcomes.

[Jamie Madigan writes about the overlap between psychology and video games at www.psychologyofgames.com. Follow him on Twitter: @JamieMadigan]

References

Anderson, C., et al. (2010). Violent Video Game Effects on Aggression, Empathy, and Prosocial Behavior in Eastern and Western Countries: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 151-173.

Ferguson, C. and Kilburn, J. (2010). Much Ado About Nothing: The Misestimation and Overinterpretation of Violent Video Game Effects in Eastern and Western Nations: Comment on Anderson et al. (2010). Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 174-178.

Gitter et al. (2013). Virtually Justifiable Homocide: The Effects of Prosocial Contexts on the Link Between Violent Video Games, Aggression, and Prosocial and Hostile Cognition. Aggressive Behavior, 39(5), 346-354.

Przybylski, A., Deci, E., Rigby, C.S., Ryan, R. (2014). Competence-Impeding Electronic Games and Players' Aggressive Feelings, Thoughts, and Behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(3), 441-457.