You've seen advertisements on television for websites and games that will 'train' your brain to be better.

Well, they work, it's not total snake oil, though they work mostly at teaching your brain to solve the puzzles in those websites and games. Elliot T. Berkman, a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Oregon and lead author on a new paper, says that training for a particular task does heighten performance, but that advantage doesn't necessarily carry over to other things. So if solving puzzles in apps is going to be your career, great. Otherwise, save your money.

The training provided in the study caused a proactive shift in inhibitory control. However, it is not clear if the improvement attained extends to other kinds of executive function such as working memory, because the team's sole focus was on inhibitory control, said Berkman.

App and website companies promoting these brain games needn't worry too much about their revenue just yet; the study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which has been shown to be rife with its own methodological problems and subjective criteria, and the work was done using college students. And, also, plenty of people are suckers, as the persistent best-selling nature of David Perlmutter's Grain Brain demonstrates.

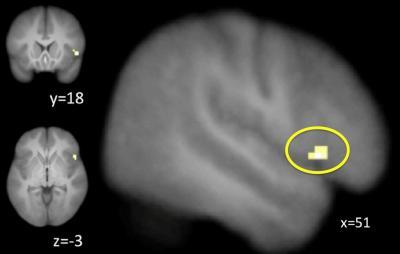

Changes resulting from training are highlighted in the brain's right frontal gyrus (yellow), based on an fMRI study of subjects in experiments at the University of Oregon. Pre-task training was found to work just for the challenge at hand. Courtesy of Elliot Berkman

60 University of Oregon students (27 male, 33 females and ranging from 18 to 30 years old, 84% Caucasian, 4% Asian-Pacific, 7% Hispanic, 5% other - University of Oregon psychology classes need more diversity) took part in a three-phase study. Change in their brain activity was monitored with fMRI. Half of the subjects were in the experimental group that was trained with a task that models inhibitory control -- one kind of self-control -- as a race between a "go" process and a "stop" process. A faster stop process indicates more efficient inhibitory control.

In each of a series of trials, participants were given a "go" signal -- an arrow pointing left or right. Subjects pressed a key corresponding to the direction of the arrow as quickly as possible, launching the go process. However, on 25 percent of the trials, a beep sounded after the arrow appeared, signaling participants to withhold their button press, launching the stop process.

Participants practiced either the stop-signal task or a control task that didn't affect inhibitory control every other day for three weeks. Performance improved more in the training group than in the control group.

Neural activity was monitored using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which captures changes in blood oxygen levels, during a stop-signal task. Activity in the inferior frontal gyrus and anterior cingulate cortex -- brain regions that regulate inhibitory control -- decreased during inhibitory control but increased immediately before it in the training group more than in the control group.

The fMRI results identified three regions of the brain of the trained subjects that showed changes during the task, prompting the researchers to theorize that emotional regulation may have been improved by reducing distress and frustration during the trials. Overall, the size of the training effect is small. A challenge for future research, they concluded, will be to identify protocols that might generate greater positive and lasting effects.

"With training, the brain activity became linked to specific cues that predicted when inhibitory control might be needed," he said. "This result is important because it explains how brain training improves performance on a given task -- and also why the performance boost doesn't generalize beyond that task."

Still, we know some brain training does work - like putting celebrities in advertisements:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.