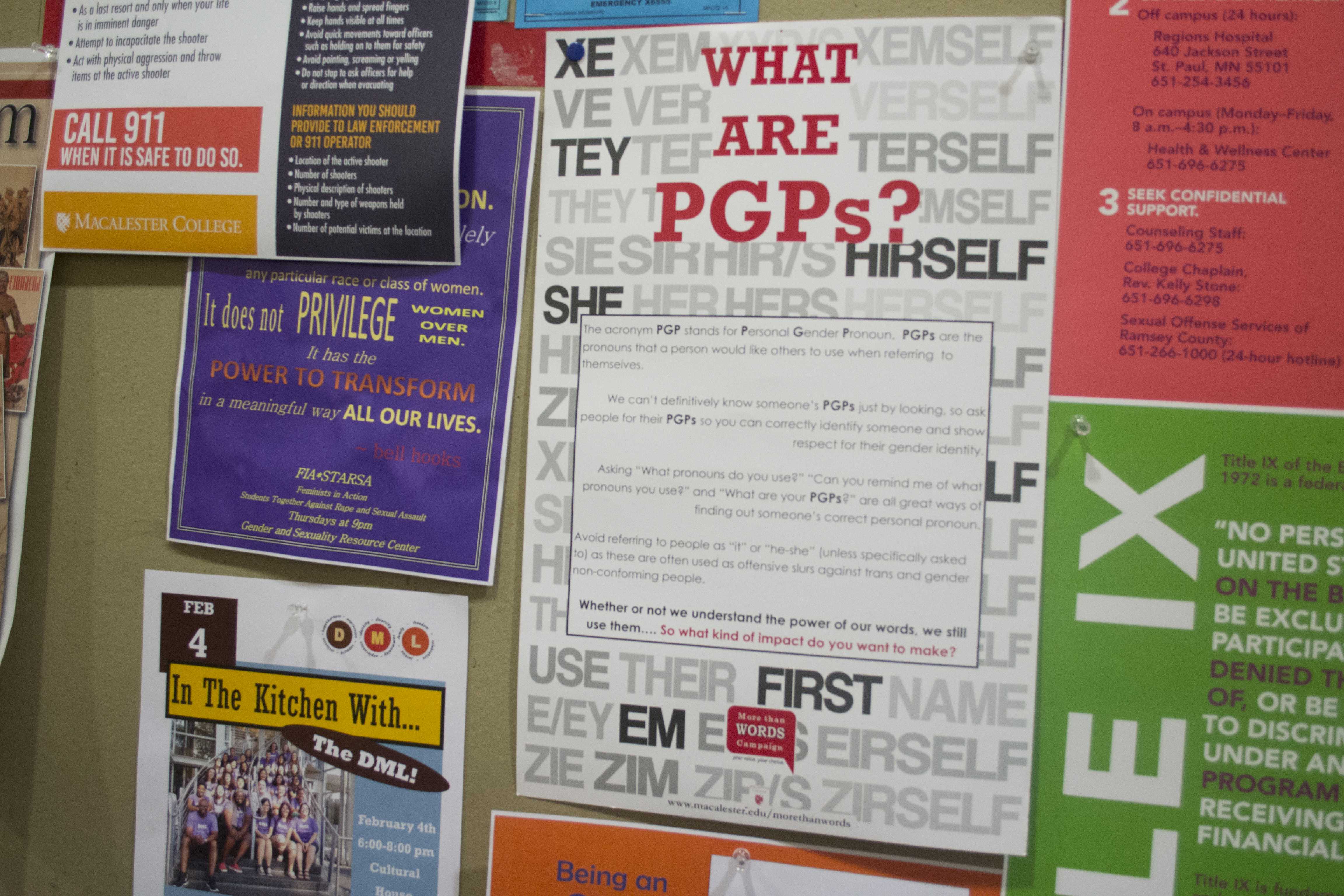

Macalester has a number of informative posters on PGPs. Photo by Will Milch ’19.

PGPs are a vital part of Macalester culture. However, this more accepting campus identity has had to be cultivated and nurtured by both the community and administration.

Professor and Chair Joan Ostrove of the psychology department offered some perspective on the history and future of PGPs at Macalester.

On the changes in the Macalester community, Ostrove wrote that Macalester has “changed a lot. I arrived in 1999, and there was no public discourse whatsoever on campus related to transgender issues, the fluidity of gender identity, etc. It’s really only been in the last two to three years that the culture here has undergone significant change, especially with respect to the intentional use of PGPs, in large part as a result of student input and activism.”

Ostrove commented on the execution of a safer and more accepting community, focusing on the intentional creation of safe spaces for people to connect with one another, citing programs like the Identity Collectives through the DML. These safer areas for discussion and discourse are, of course, in addition to “trying to create a culture of using PGPs, having all-gender bathrooms and recognizing diversity in gender identities [which] has been important, I think, to demonstrate more openness and to provide safety for non-binary and trans individuals,” as Ostrove put it.

Ostrove, upon reflection on the use of PGPs in the classroom setting wrote, “I think it’s important to provide context for the use of PGPs, focusing especially on the roles of sexism, the socialization of boys and homophobia in setting up very rigid expectations and boundaries related to gender that have particularly harsh consequences for people who do not conform to cultural expectations. The use of PGPs is one way to signal that not everyone’s gender identity can be discerned by external cues, to disrupt the use of assumptions in gendering other people and to allow individuals themselves to tell those around them what kind of gender pronouns they prefer.” Professor Ostrove went on to write, “One concern that emerged for me, in a discussion with a colleague, is that the ‘rote’ use of PGPs — while offering an important space to non-binary individuals and decreasing the possibility of misgendering — may force people (regardless of gender identity) to come out who do not necessarily want to, or to further marginalize people who are the only non-cisgender person in the space. I don’t think there are easy answers, and I recognize and respect that trans students have been most vocal about requesting the use of PGPs during introductions, but we need to be really aware of why we are engaging in this practice so that we don’t further marginalize people or single them out.”

Ostrove offers up a constructive way to combat a situation where an individual feels pressured to share their gender identity: “After I give my short talk about the context for using PGPs during introductions on the first day of class, I invite people to share their PGPs if they want to. I think making it optional, but opening up a sincere invitation, might help.” However, Professor Ostrove acknowledges, “It’s not a perfect answer, and I think it’s important for us all to continue to think about it, and I recognize that as a cisgender woman who has hardly ever been misgendered in my life, I am coming from a position of privilege in trying to sort out these issues.”

If a more open environment surrounding the fluidity of gender was achieved within only a few years in the small community of Macalester, it is indeed a hopeful sign that we, as a community, can cultivate an increasingly more accepting culture both on campus and in the wider world.